Jo Sandman was not only a witness to the historically important experimentation that shaped mid to late 20th century art, but also an active participant . A student of both Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell, she was in residence at Black Mountain College with Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly and later worked for Walter Gropius. Trained as a painter, she went on to create innovative drawings, photography, experimental sculpture and installation works, which were exhibited widely and are now in the permanent collections of numerous museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the de Young Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco, and many others. In addition to numerous artist residencies and teaching fellowships, she taught at Wellesley College and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Significant awards include fellowships from the Massachusetts Arts Council and the Bunting Institute at Harvard, as well as grants from the NEA and the Rockefeller Foundation. Over the course of a long career, she exhibited widely and in 2022 was featured in a career retrospective Jo Sandman: Traces at the Black Mountain College Museum in Asheville, NC and the exhibition Helen Frankenthaler and Jo Sandman/Without Limits at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, ME.

The Music Shed, 1951, digital print from scan of original gelatin silver print

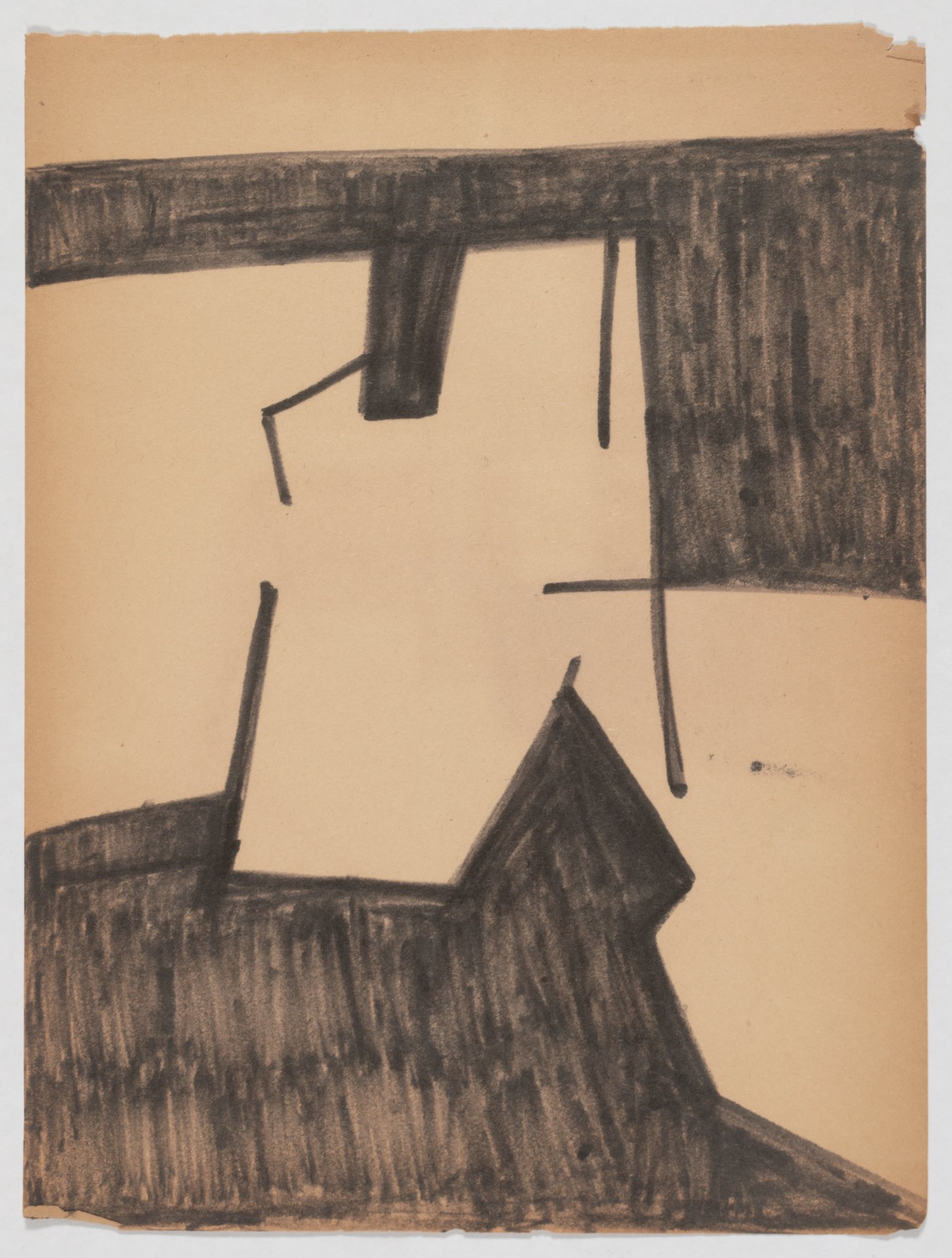

Untitled, c. 1951-2, oil on canvas,

30 x 24 inches,

Black Mountain College

Untitled, 1952, oil on canvas,

40.75 x 32.5 inches

Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College, Summer 1951

Although Jo Sandman didn’t get to Black Mountain College until 1951, she’d long wanted to go. Growing up in the culturally rich suburb of Newton, Massachusetts, she regularly visited museums and attended concerts with her artist mother and musically inclined father, and was only sixteen when she first applied in 1948 after hearing Black Mountain was “an excellent progressive school.” However, when the admissions committee responded negatively to Sandman’s portfolio and asked to see writing samples—not surprising considering she was competing against a sudden influx of WWII veterans like Robert Rauschenberg who’d previously attended art school and had funding from the GI bill—Sandman asked for her work to be returned and told Black Mountain she had other plans. After disappointing stints at the Connecticut College for Women and Emerson before settling at Brandeis, she re-applied and was finally accepted as a painting student for the summer of 1951. It was only then, she later said when speaking about an experience that proved to be crucial that she “really decided to become an artist in a serious sense.”

Black Mountain was different from other schools she’d attended, both geographically and in other ways. Immediately upon arrival she went out to pitch hay and then spent her first evening sitting around with other students reading James Joyce aloud. Delighted with her very own studio space, she imagined painting all day with only a break for French class. “I like this intensely,” she wrote in her first letter home. Instead of the arty characters and bohemianism she’d encountered at Brandeis, Sandman particularly admired the industry of the people around her, their “attitudes and outlooks of life in general and the reason for being at Black Mountain in particular.” “Here they produce” she wrote. “Am very sure all this is right for me.”

It would be hard to overstate the quality of instruction. In addition to French, Sandman took drawing with Joseph Fiore, anthropology with Paul Leser whose Socratic teaching method she found “simply jolting,” and photography with Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. Callahan lent Sandman his tripod and it was under his direction that she photographed the woodland cubicle where students practiced music. However, Siskind left an indelible mark. Thrilled by his pictures of decayed posters and stained wallpaper, Sandman saw that photography could go beyond mere documentation towards the kind of flattened abstraction she was trying to achieve in painting.

“Originally I planned to take many courses,” she wrote her parents, “because I felt so enthusiastic. But I feel now…I am here to paint, and I’ll stick to that.” This was difficult in a school that encouraged multidisciplinary collaboration. “For instance,” she wrote in a letter home, “Nick (a student) did a modern dance. Shahn designed a pattern to be printed on Nick’s chest to make the design of muscle and light better, in the body movement. Shahn’s design was a sort of hieroglyphic affair, which he set down in color on paper. Olson, seeing this, wrote a poem. Litz (dance instructor) hearing the poem is doing a dance on it. And so on.”

During July she studied with Ben Shahn, a Social Realist seemingly out of place in a school where the painting was mostly abstract. Yet, Shahn played with the tools of abstraction—the saturated colors, the distortion, and flatness—and believed that “the public function of art has always been one of creating community.”

However, despite her interest in ideas Shahn expressed in his lecture Aspects of Realism and Sandman’s earlier training with the Boston figurative expressionist Arthur Polonsky, she was committed to abstraction by end of summer. When Robert Motherwell took over the class in August—he and Shahn overlapped only by a few days, perhaps as an administrative effort to manage discourse around the merits of realism versus abstraction—Sandman was in her element. “Robert Motherwell is red hot,” she wrote. Working alongside fellow classmates like Suzi Gablik, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly, she enjoyed an exhausting, yet productive time, not even wanting to find relief from the summer heat by going swimming. There was simply too much to do. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked so hard,” she wrote. “My painting is getting better, and I love doing it more and more.” She expressed regret for anything that took her out of the studio. Prior to Motherwell’s arrival, she’d enjoyed harvesting tomatoes and squash, pitching hay, or rebuilding a collapsed footbridge, finding it the “good wholesome work of everyone working in teams.” But now “dish crew and other duties is annoying for the first time…it gobbles up precious hours.”

Yet her regret did not extend to the evening hours after dinner. Sandman wrote of a magnificent dance recital performed by Katherine Litz to one of Lou Harrison’s compositions and described a concert by David Tudor as something she simply could not get over. “The quality of work being produced…it’s phenomenal.” Although John Cage was not in residence, his protege David Tudor performed Cage’s work and encouraged students to experiment with a temporarily altered or “prepared” piano. “Last night a performance of music compositions done by students this summer was given,” she wrote. “Most of it was rather esoteric, some quite percussive, and rather exciting. The last piece was played on the strings of the piano, not the keys. Two pianists played by plucking and using two implements from the milk house to bang on a series of strings—a counter scraper and a wiry brush. Inside, I was hysterical, it seemed so strange and funny, but the music was actually good.”

Willingness to entertain experimentation by others, as well as experiment herself, was key to Sandman’s experience at Black Mountain—that and a desire to work hard and produce. “I love being here,” she wrote. “Though we work hard, it still seems like a good vacation. And one can’t help being productive. It’s the way of life here.” In a giddy description of her final days at the college, she wrote of a “dance festival by students, later in the evening an exhibit of paintings by Joe Fiore (instructor), a reading of prose and poetry by Olson’s students, and the showing of an experimental film. Tomorrow, another experimental film, and our photography exhibit. The next night our play, Thursday a student art exhibit, and then? Everyone who has been here for the past three of four years agrees that this has been the most productive summer they’ve ever seen. And I’m sure it’s been my most productive summer.”

Untitled (photogram), c 1950s,

5.5 x 4.325 inches,

mounted on board

Untitled (drawing from model stand 1), c 1952-3, Marker on newsprint, 11.75 x 9 inches

Sand and Rock, Photograph, c 1950s, 2.25 x 2.25 inches, from a contact sheet

Berkeley, California, 1953-55

After a year Sandman left to enroll in the graduate program at the University of California at Berkeley, which was a good fit. Although Hofmann had only taught there for two summers in the early 1930s, his ideas—a perfect synthesis of German Expressionism, Fauvism and Cubism—still held sway. As only the second university in the country to open an art department, Berkeley held a reputation for intellectual rigor, requiring students to take art history in addition to studiocourses. Hofmann’s protege Erle Loran ran the art department, making Berkeley a good place for Sandman to “make sense of the heavy and intense information”[5] she’d received in New York. Once in graduate school she felt she could make those ideas her own.

Working alongside classmates Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown, Sandman’s work took shape. Northern California was then a hotbed of painting activity, said by some to rival New York. Mark Rothko and Clifford Still taught in San Francisco in the late 1940s, influencing students like Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, and David Park who all subsequently maintained studios in Berkeley. Although the group was later recognized for figurative work as San Francisco Bay Area Artists, Abstract Expressionism was still the dominant mode in the area when Sandman was in the art program at Berkeley. “I would paint feverishly,” she said in a vivid description of her painting process. “Then stop, pull away, smoke a cigarette…you study it for hours. Then you do something. Then you wait until the next day. Most of my time painting was studying the work. I had to make sure the surface stuck, that there weren’t any deep holes.”

Studies with Hans Hofmann, Provincetown and NYC, 1952-53

Sandman wanted to stay at Black Mountain, but was finally resigned, perhaps at the urging of her parents, to finish up at Brandeis. After graduating, she demonstrated an unerring ability to put herself in a good place and went to Provincetown for the summer of 1952 to study painting with Hans Hofmann. Instead of a faculty of artists, musicians and dancers who’d worked collaboratively at Black Mountain, there was only one instructor at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Art. Students were expected to focus on a single medium, mostly easel painting, but that was fine with Sandman who wanted to paint. In September she moved to New York to continue her studies, working as Hofmann’s part time registrar in exchange for tuition at school in the Village.

“Mornings we’d work from a life model,” Sandman remembered, “drawing from the figure not in any literal traditional sense.” Instead, Hofmann urged students to look through a Cubist lens in order to define the contours and depths of their compositions. Much has been written about Hofmann’s theories of push-pull, the expanding and contracting forces found in the compositional opposites of warm against cool colors, or geometric shapes against fluid ones. However, Hofmann was not Sandman’s only teacher. She was a member of The Club, a loose affiliation of artists who met in a rented loft on East 8th Street, only a block from the legendary Cedar Tavern where they went after meetings. Originally limited to men, The Club began to admit women as dues paying members in 1952 and Sandman joined about the same time as Elaine de Kooning and Joan Mitchell. Here these young women could connect with painters like Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, and Franz Kline, as well as intellectuals like Harold Rosenberg, John Cage, and Sandman’s former painting teacher from Black Mountain Robert Motherwell.

“I was strongly influenced by Robert Motherwell.” Sandman enrolled in his evening seminar at Hunter College even though “it didn’t involve actual painting but was about painting.” Motherwell discussed artists like Willem de Kooning, Arshille Gorky and Jackson Pollock and “critiqued their work in a positive manner.” He familiarized students with the conflicting critical opinions of Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, giving Sandman “a sound philosophical basis...to view and think about painting.” New York also provided opportunities to meet up with old friends from Black Mountain. Sandman’s former roommate Selma Weisberg was at NYU and regularly joined her for lunch. The dancer Tim LaFarge traveled often to New York before becoming a founding member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Together the friends went to exhibitions of painters they admired—de Kooning, Gorky and of course Motherwell. “De Kooning,” she wrote her mother with the heartfelt conviction of youth, “is without a doubt one of the great painters of our time.”

Clichy, c. late 1950s-early 1960s,

Oil and Magna on canvas,

40 x 51 inches

Untitled, 1967, Torn paper collage with drawn pencil, 14 x 11 1/5 inches

Mach 5, oil and enamel on canvas, c 1959-1963, 51 x 40 x 2 inches

Boston, mid 1950s-60s

After graduation and a series of life adventures, she returned to Boston for what she thought would a short visit but then decided to stay. Her father offered to pay for some practical training at Katharine Gibbs, known as the Harvard of secretarial colleges, but his daughter was determined to stay focused on art. She entered a teaching certification program at Radcliffe and earned a master’s degree in education in 1956. While there she met Walter Gropius, one of Josef Albers’ colleagues from the Bauhaus who’d ended up at Harvard. Gropius had also taught at Black Mountain in the 1940s and hired Sandman work at his firm The Architects Collaborative (TAC). After years of waitressing, she was gratified to finally be able to make a living with art. She was a color consultant and designed tiles and murals for schools and apartment buildings, work that continued even after she took a job teaching at Wellesley College in 1956.

However, her experience at Black Mountain continued to occupy her thoughts. The summer before she started at Wellesley, Sandman traveled to Mexico to investigate the murals of Diego Rivera, whose assistant Jean Charlot had painted frescos on cement pylons under the Studies Building at Black Mountain College. By visiting the country, Sandman was following in the footsteps of artists and writers who’d preceded her, many with Black Mountain connections. When Sandman arrived at the college in 1951, Charles Olson had just returned from six months in the Yucatan and was certainly “one of the most dynamic men on campus...he and his wife spent a lot of time living with the Mayans,” she wrote. “He has lots of theories on them in relation to language and literature.” Olson’s “glyph” poems, inspired by Mayan hieroglyphics, were the basis of his collaboration with Ben Shahn that Sandman witnessed and perhaps to convince her parents that she was not missing out on traditional western pedagogy, she also wrote that Olson was “completely grounded in classical education” and that everyone at the college felt “knowledge of past achievement is necessary for a starting point from which new achievements arise...Although little formal discipline exists here, there is a great deal of self-imposed discipline.”

This kind of self-imposed discipline would eventually stand her in good stead. Sandman got married in 1958 and with the support of her husband Robert Asher continued working for Gropius and teaching at Wellesley until the birth of their first child in 1961. Yet even with young children, she continued to make art. Her daughter Kamala remembers a neighbor coming to watch her and her younger brother Tom, not learning until much later that her mother would kiss them goodbye, leave by the front door, and then surreptitiously walk around the house to enter her studio through the basement bulkhead. When asked how she managed, Sandman responded as any working mother might by saying “with difficulty.” However, despite the distracting cries and sounds of small footsteps overhead, she persevered. “I did less painting because of the demands of the situation, but I always hung in there…so the work developed in kind of a curious way.”

Collage was the curious work to which Sandman referred, making it possible for her to navigate around the needs of kids. But collage was also significant to how art developed during the twentieth century. “Smuggled into Black Mountain by Josef Albers,” it helped shape a modernist aesthetic. While Sandman never studied with Albers, his preference for mass produced colored paper and found materials was in the school’s DNA. The “cutting, pasting, disassembly, and reassembly—essentially the operations of collage—were all by-products of the primary color-theory lesson,” wrote curator and art historian Helen Molesworth. Collage techniques also found their way into the work of Motherwell and Rauschenberg, the dance choreography of Merce Cunningham, the musical compositions of John Cage, and finally the writing of Charles Olson and Robert Creeley. But for Sandman, it was not only a way to get back into the studio after children were born, but also a serious pursuit which afforded opportunities for her to make art “in a passionate way that was really fun and not just work.”

Folded Drawing #15, 1973, Folded fabric drawing, white duck, 37 x 22 4/5 inches

Untitled: Removals, 1976, Collage, insulation foil, 15 x 17.25 inches

1970s

However, she felt she’d “hit a snag” and that Abstract Expressionism had become a dead end. “I loved painting,” she said with regret. “I respected the whole ethos. I loved working gesturally. I loved working with inchoate material from one’s own inner being. I loved color and I was good at it.” However, like many painters in the late 1960s she was surrounded by a complicated explosion of new media, installation and performance that challenged the very idea of painting. This was not impossibly distant from what she’d experienced at Black Mountain. Musical performances on prepared piano, experimental films, and Olson’s glyph poems laid the groundwork for John Cage and David Tudor’s 1952 staged happening with Merce Cunningham, M.C. Richards, Robert Rauschenberg, and others—an unscripted event that many feel was partially responsible for the aesthetic turbulence in the 1960s." Intimidating and off-putting to some, it was exciting for Sandman who had always felt compelled to “go beyond what has been done in the past” and seek new ways to create “in a modern idiom.”

She began experimenting with her painter’s supply of Belgian linen. Instead of stretching it, she used a handheld iron to crease the material and then negotiated with a dry-cleaning plant to use their industrial press. Her sharply folded linen grids were of immediate interest to collectors and curators engaged by such minimalist artists as Carl Andre, Sol Lewitt, and Dorothea Rockburne. None of that group had ever studied with Josef Albers and neither had Sandman. However, all were indirectly influenced by his Homage to the Square and work with geometric abstraction. When Sandman became aware that she and Rockburne were working in similar ways, she experienced momentary panic. The two women were nearly the same age and although both had attended Black Mountain in the early 1950s, their paths never crossed because Rockburne had been absent the summer Sandman was in residence. Yet Sandman feared comparisons would be inevitable.

“My god,” she remembered thinking, “someone else is folding. What am I going to do?” But after reading about Rockburne’s work and looking at reproductions, Sandman decided that this wasn’t an issue. “Screw it,” she thought. Fonder of Rockburne’s grease and carbon paper work than her folds, Sandman concluded that it was a little like scientists in South Africa running the same kind of experiments as scientists in America. “Discoveries can be made simultaneously in different parts of the world,” she told students. “It happens all the time.” What really mattered was how individual artists handled experimentation in their own studio.

“I keep on making art because it means repeatedly taking risks,” she said early on and throughout the 1970s it seemed like Sandman’s risks were paying off. Picked up by galleries in Boston, New York, and San Francisco, she exhibited both nationally and internationally. Her large, 56 inches square grids of Belgian linen were pinned directly to the wall, while smaller experiments with cotton duck were framed. Walking the line between drawing and sculptural relief, these pieces touched upon conceptualism by asking viewers to visually retrace the raised and sunken folds to understand the history of their manufacture. Yet conceptual ideas were never more important than her final aesthetic. Sandman loved the sensuous feel of material and was delighted by how colors would subtly shift when light fell across a folded surface.

“I had been a dedicated Abstract Expressionist,” she mused. “And went through a whole lot trying to kick that.” Speaking to a group of students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1979, she confessed to periodically clearing up debris in her loft every three or four months. She’d then take paintings out of the black plastic garbage bags where they’d been stored, unfold, and staple them to the walls. Unplugging her phone, she let the paintings inhabit the studio for a while to simply have a “communion with old friends.” Then, after working on them, she’d let them dry, fold them back up, and put them away. Calling herself a closet painter, Sandman used these sessions as a way to explore her past and move forward. “Historically, it just didn’t make any sense for me to be a third or fourth generation Abstract Expressionist. I couldn’t support that notion any longer, that this was a viable form when it seemed to have exhausted itself for others as well as for me.

Folded linen initially pointed towards a path forward, but Sandman grew tired of taking materials to the dry-cleaners and then back to her studio, where she could unfold, look, and then throw away what she didn’t like. It was time consuming and wasteful now that her painter’s stockpile of Belgian linen was running low, and she once again turned to Black Mountain for inspiration. The school encouraged students to use whatever material came to hand, so Sandman started using rolls of silver barrier foil that she’d found at the lumber yard. Cheap and readily available before the energy crisis, this industrial material was composed of beige kraft paper sandwiched between sheets of silver foil on one side and a sticky black coating on the other. Sandman made subtractive Removal drawings by picking away at the black layer with a metal stylus, gratified by the act of physically making a mark, even in reverse. “I was recapturing the spirit of my early training,” she observed. “It was something I needed to do.” Although spare and minimal, her Removals were not minimalist. Instead, their shadowy, enigmatic appearance reflected Sandman’s belief that art might have the capacity to move viewers “in a manner akin to magic.” By excavating drawings from a core of laminate material, she managed to dodge an “inevitable split between conception and object” with nocturnal landscapes that opened up “a dialogue between art as process and art as illusion.”

Tarp Series: Glyph, 1983, Collage, found painter's drop cloth

Untitled: Degrees of Desire, 1988, Paint, plaster, tar on museum board, 18.75 x 15.75 inches

Artifacts of Air, Suite III, No. 8, 1989, Caulk on emery paper, 11.375 x 9.375 inches

1980s

Fascinated by the interaction of thin beige lines against an expanse of black, Sandman began cutting up Removals, reawakening her earlier interest in collage. She returned to fabric as a material, abandoning pristine Belgian linen for stained, and splattered drop cloths that she got from “crusty old house painters who had crusty old tarps.” Hacking into the heavy canvas with scissors, she realized a kind of energy trail, and created monumental installations by tacking strips of used tarp directly onto the walls of entire rooms. Random layers of thin paint might invite comparisons to Helen Frankenthaler’s soak stain paintings, but art historian Pam Allara argued that Sandman’s drop cloth installations were essentially drawings that explored relationships of “line to plane, plane to volume” and found Sandman’s Illustrations for a Poem without Text or Glyphs, a series of smaller collage pieces to be both gestural and in possession of “a strong calligraphic quality.”

Critically compared to Motherwell, Sandman’s Glyph collages can also be traced back to Olson and her summer at Black Mountain, as well as to the years spent considering Hofmann’s theories about push-pull and negative versus positive space. In an NPR radio review of a large tarp installation at the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, the critic Rebecca Nemser concluded that “Jo Sandman is a painter who doesn’t paint.” Sandman couldn’t disagree. Motherwell and Hofmann both stressed the importance of maintaining the integrity of the picture plane. Sandman was simply transferring their teaching on formal issues, as well as her own love of sensuous painting, to unconventional mediums that did not involve paint.

Industrial material intrigued Sandman. She stockpiled electrical wire, roofing tar, various grades of sandpaper, and rolls of window caulking purchased at the hardware store. One day while sitting in her loft sketching, she noticed dancing particles of dust in the rectangular sunbeams that fell from the skylight. In a perfect description of how an artist might become inspired, she remembered these minute dust motes floating down “in currents of air, jiggling, bumping and gently free falling, all in slow motion. I wondered what free form these particles would assume if I could capture, enlarge, and materialize them. Closely observing this little illuminated scene, I let my imagination roam. After a time, shapes began to emerge, looking very much like an abstract comic strip of the mind or story boards for an animated film. These quirky shapes suggested their final material form, caulking compound on emery cloth...a gritty, industrial version of velvet [that] served as a good background to grip the clay-like line or squiggle.”

Roofing tar was less easy to work with, but Sandman liked the challenge, feeling that “the inherent difficulty in handling the tar...was “offset by its plastic potential.” She described eccentric forms emerging from her struggle with the sticky material. In addition to large tar drawings with spare configurations of line, Sandman also made more modestly sized works with exposed areas of white in the center. Degrees of Desire speaks to a poignant longing for human touch in its sensuous depiction of human lips or parts of the female anatomy. Sandman also likened the negative white space of these small works to the shutter of a camera opening to take “snapshots of arrested idiosyncratic forms.”

Untitled, 1992, Collage, sandpaper, paint, and tar, 17.75 x 14.75 inches

Tar Drawing Series #2, c. 1990s

Roofing tar, archival paper on museum board, 52 x 40 inches

Small/Big, 1992-1994

Automotive radiator hose with plaster and wire, 4 x 2 x 2 inches

Untitled (Continuities), 1992-1994

Automotive radiator hose with plaster and wire

Echoes from the Garden #2, 1993

Assemblage (wire, plaster, and rubber) on museum board, 15 x 13 inches

Rubberworks, 1999

Black rubber (inner tube) and rivets on museum board, 17.25 x 14.25 inches

1990s

Sandman found unconventional art supplies everywhere. One day while sitting in a service station waiting for her car to be repaired, she looked at a selection of radiator hoses hanging on the wall and saw them as “sensuous and exciting.” After her car was fixed, she asked the technician if she could buy a few hoses. Sure, he told her, but wanted to know for what kind of car. When Sandman told him she wanted to choose them on the basis of shape, and he thought she was kidding. “No,” she said, “I’m an artist and I’m going to play with them.” He reluctantly sold them to her. With thick rubber walls and measuring about two inches in diameter, the hoses were perfect containers for plaster of paris that she let harden before cutting into it. Much as she’d excavated drawings from insulation foil by lifting off segments of black coating, the cuts revealed geometric, glyph-like shapes at their core.

Sandman made arrangements of these hose shapes, most notably in Continuities, an eighteen-foot installation at the Danforth Museum that snaked across the wall like fragments of a hieroglyphic language written out in a sculptural sentence. Sandman began edging away from pure abstraction towards representation in works that she excavated from Continuities, such as the quirky little figure Small/Big or in her Echoes from the Garden collage reliefs that placed left-over plaster and rubber hose pieces onto grids in off-kilter ways. Like many artists who’d embraced minimalism, Sandman wanted to acknowledge the importance of the grid, yet somehow disrupt and subvert it. Echoes from the Garden signaled her desire to escape the rigidity and cold reserve of minimalism and take Voltaire’s advice to simply tend her own garden.

Going back to the garage, she seized upon inner tubes. Easier to cut than heavy tarp, the rubber yielded unexpected shapes and homey objects. ”A teacup, a water kettle, a girl’s skirt, a pair of boy’s britches.” Since Berkeley, Sandman had admired Richard Diebenkorn’s ability to incorporate abstract elements into representational urban landscapes. She was therefore delighted when simplified, yet recognizable shapes fell from the lines she traced with her scissors and mounted these charming domestic items on archival board, taking care to fasten them down with rivets to acknowledge an industrial source.

Sandman enjoyed domesticity, remarking that having babies might have slowed her down her development as an artist, but certainly not her development as a human being. “I would never have wanted not to have done that thing.”[23] But as the children grew older, she started teaching again, first at Wellesley and then at the Massachusetts College of Art. She enjoyed artist residencies. She and her husband also traveled extensively, and she worked on archeological dig in France. However, her most meaningful find came mid-career as her work underwent another shift.

“After years of working abstractly,” she said, “I became interested in using the world of appearances--the real world--to inform my work...The issue became one of how to accomplish this using the lens of my own sensibility, one which avoids the literal, and which invariably yields up spare, stripped-down images.”

An answer came to her while visiting the volcanic island of Papua, New Guinea. Walking along the beach, Sandman was startled to see “faces” staring up from the sand. She began collecting broken chunks of rock, coral and lava that seemed to possess human features, some worn smooth by water, others pock marked, scarred, and misshapen. She found them “strangely compelling, even in their incomplete state of missing, disarrayed features, and jagged outer contours. They seemed to reference primitive masks...” and once back in the studio, she used the smallest of drill bits to define emerging faces. Each had distinct personalities. When finished carving out their faces, Sandman began using them to play around with light sensitive paper before moving on to photo copiers, cameras, and computers.

Although she studied with Callahan and Siskind and is known to many as a photographer, Sandman doesn’t consider herself one. After years of working abstractly, photography represented a way for her to portray the human figure without becoming too literal. By layering duplicate faces for Twice or fracturing and reassembling them for her monumental Geos, Sandman could explore the spareness of her own sensibility. Whether experimenting with direct cyanotype or creating Van Dyke Brown photograms for Memento Mori, she was using an “antique process not to create a concrete document, but rather to create a metaphor of the spirit.” The bony figures in Metamorphose speak to an artist’s ability to move forward and be transformed. By drawing skeletons in conte crayon over wraithlike heads floating in space, Sandman managed to not only ground them, but also confirm her growing interest in creating recognizable images.

Unfortunately, she developed carpal tunnel syndrome, perhaps as a result of drilling into hundreds of bits of coral. Yet she managed to turn the tools of her diagnosis into art, collecting x-rays of her own body, hands and wrist, and eventually dental records, which she then scanned into her computer and digitally manipulated before printing. She also experimented with x-rays donated to her by medical professionals before privacy laws prevented that. “There was no limit on what she thought was interesting,” observed the photographer Gus Kayafas, who produced the limited-edition portfolio Light Memory. “If curiosity took her there, she went.” Yet while Sandman’s x-rays began life as a diagnostic tool, the images she realized from them were far from clinical. “My project is to invest this material with an emotional life,” she explained, and “to bring depth and humanity to the individual.”

For Sandman photography was an expressive medium that basically allowed her to draw with light. “The core of my work is based in drawing,” she said. “I am continually drawn back to drawing as a method of investigating the world through observation and imagination.” This had been a constant over the years. She had referred to the foil removals and tarp pieces as drawings, as well as the imagined dust particles she outlined with window caulking. Now she could use photographic light drawings to explore a world that was internal--literally in the case of skeletal bones in Light Memory and metaphysically in the disembodied heads of Memento Mori.

Thoughts of light naturally led to a consideration of heat. Sandman began to experiment with lit incense and 4th of July sparklers, waving them over facsimile paper to realize heat generated lines and shapes, which she then scanned and digitally enhanced to create Thermal Drawings.These works clearly reference the kind of expressive energy demonstrated in Sandman’s painting. “While my work with x-rays is preconceived and exacting,” she remarked, “these drawings are spontaneous” and come “from an impulse to use unimpeded gesture.”

Taking it one step further, she experimented with wood burning tools to make singed paper collages entitled Ignitions or Hephaestus’ Breath. “These drawings or mappings of landscape are formed by the alchemy of fire,” Sandman wrote. Setting layers of parchment paper aflame, she watched as the material began “to seek its limits” and “define its boundaries” by “meandering around the circumference.” Delighted by the unpredictable twists and turns of flame, she compared fire to water and how “coves, inlets and bays make their incursions into the land mass.” Again, she was pleased to see evidence of manufacture in the flecks of ash and “delicate trail of the activity of combustion” in works that “openly display the process by which they came into being. Defined by fragility, they speak metaphorically of a search for the shape of loss.”

Much of Sandman’s work explores transience, but in photography she was able to speak “to the tentative nature of life” and “our limited time on earth.”For Serpents, a series of platinum/palladium photogram prints made in 2014, she arranged snake skins purchased from the New England Wildlife Center on photo sensitive paper, using a technique similar to the one Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil had used for experiments with cyanotype at Black Mountain in the 1950s. Her alphabet-like shapes also reference Olson’s work with glyphs, a motif that Sandman had previously carried forward into her tarp and tar drawings. While Serpents was one of the last formal experiments she carried out in her studio, this series of snake prints speaks most pointedly to lessons learned in 1951. Here, and in each part of a career that spanned more than six decades, traces of Black Mountain can be found. Sandman freely experimented with unconventional material. She was willing to take risks. And, although sometimes pulled between conflicting desires to work both abstractly and with recognizable imagery, she never wanted to settle comfortably into what had been done in the past. Instead, she was an artist with a profound need to slough off the old in a continual search for new ways to create in a contemporary, but not necessarily modernist idiom.

Geo series #38, 2001, Photographic prints mounted on Sintra PVC panels, 58 x 48 inches

Untitled [Ignitions 8] from the series Ignitions/Hephaestus' Breath, 2000, Burned paper collage, 17 x 14 inches

Light Memory #4, 2006, Toned gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches

Light Memory #3, 2006, Toned gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches

Thermal Drawing #12, 2007, digital pigment print, 22 x 17 inches

Serpents #1, 2012-2014

Platinum/Palladium Photogram translated into a digital print, 22 x 17 inches